|

|

- Search

| Gyne Robot Surg > Volume 4(1); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

The second Asian Summit on Robotic Surgery (ASRS) was convened in Singapore, 12 November 2022. This meeting was well attended by speakers and participants from around the region. The Gynecology tract of the ASRS 2022 was supported by the Asian Society for Gynecology Robotic Surgery. Co-chaired by Dr. Jeslyn Wong of Singapore, and Dr. Hyewon Chung of South Korea, the Gynecology program saw experts share their experiences, tips and surgical pearls with enthusiastic participants from the region. This article summarizes the key topics that were discussed during the meeting.

The second Asian Summit on Robotic Surgery (ASRS) was convened in Singapore, 12 November 2022. This meeting was well attended by speakers and participants from around the region. The meeting was divided into three main tracts: urology, general surgery, and of course, gynaecology. The gynecology tract of the ASRS 2022 was supported by the Asian Society for Gynecology Robotic Surgery (ASGRS). Co-chaired by Dr. Jeslyn Wong of Singapore, and Dr. Hyewon Chung of South Korea, the Gynecology program saw experts from Asia share their experiences, tips and surgical pearls with enthusiastic participants from countries such as Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, South Korea and China. The program began with a welcome address by Dr. Joseph Ng, and congratulatory messages from Professor Chi-Heum Cho, President of the ASGRS.

The first session ŌĆ£Meet the ExpertsŌĆØ was chaired by Dr. Aziz Yahya of Malaysia.

Dr. Mee-Ran Kim began the session with an engaging multimedia presentation about her experience in performing robotic adenomyomectomy for young patients in the reproductive age group. Adenomyosis can be a debilitating condition, resulting in severe dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia. Adenomyomectomy is often performed with improvement in patient symptomology, via an open approach. With surgical robotics, Dr. Kim was able to demonstrate good surgical outcomes in her patients, although pregnancy outcomes after robotic adenomyomectomy still needs to be studied further.

Dr. Tae-Joong Kim shared his journey transitioning into minimal invasive surgery (MIS) as a gynecologic oncologist. Being motivated by the intention of providing the best care for his cancer patients, Dr. Kim described his learning journey in MIS, starting with conventional laparoscopy and then surgical robotics. Conventional laparoscopy presented a much steeper learning curve compared to robotic surgery. Having learnt from the leaders of robotic surgery around the world then, Dr. Kim adapted these procedures to produce his own technique in the service of his patients in Korea.

The second session ŌĆ£Experts know-how in robotic Benign GynecologyŌĆØ was chaired by Dr. Rooma Sinha of India, and Dr. Suresh Nair of Singapore.

Large specimens for ovarian masses are those with diameters between 5-15 cm. Masses greater than 20 cm are named ŌĆ£giantŌĆØ. For the uterus, most studies would consider 15 to 16 weeksŌĆÖ gestation or a weight more than 500 g as large uterus. Dr. Rebecca Singson shared that limitations of MIS with large specimens would include restricted visualization and access to vascular pedicles, decreased manoeuvrability, increased risk for hemorrhage and bowel/urinary tract injuries, longer operative times and difficulty with uterine extraction. High epigastric port placement, use of 30-degree scope, surgical smoke evacuators, the use of tranexamic acid, oxytocin and cell salvage system, adhesion barriers, ExCITE technique were discussed as solutions to these challenges when performing robotic surgery for large specimens.

Although minimally invasive to the patient, robotic surgery turns out to be largely invasive to climate change due to the manufacture, transport, utilization and disposal of the single-use instruments, plus the carbon dioxide and anesthetic gases used for each surgery. Dr. Singson also suggested that as surgeons, we have to make a stand and request that all our medical devices and supplies from here on should be reusable, recycled or composted.

Robotic hysterectomy (RH) is one of the most common robotic procedures for gynecologic cancers as well as benign disease. The technical advantages of robotic surgery, including improved surgeon dexterity, surgical precision, visualization, and ergonomics, have allowed surgeons to perform hysterectomy more easily and safely compared to laparoscopy. Dr. Jiheum Paek delivered a lecture regarding various approaches for RH using single-site and multi-ports. In order to maximize the pros of RH, surgeons should consider how to get both space and visual field during surgery. Enough space is related to the proper port placement. According to the size of the uterus, surgeons had better decide to use single-site platform at the umbilicus or high multi-ports placement above the umbilicus. In addition, it is critical to reduce hemorrhage during surgery to get optimal visual field. For that, the use of Vessel Sealer Extend may be considered, and surgeons need to do meticulous surgical dissection when possible. The most important things for optimal surgical outcomes are to have both surgical consistency and reproducibility.

Dr. Rooma Sinha began by speaking on endometriosis. It is one of the most challenging surgeries for a gynecological surgeon. Fibrosis due to chronic inflammation involving the adjacent vital structures increases the chance of injury and incomplete excision of the disease. Minimal access is the cornerstone for surgical treatment. However, many surgeons find it difficult to do this with conventional laparoscopy. Robot-assisted surgery has emerged as an additional surgical tool for the management of endometriosis [1]. Incomplete resection is the main cause for persistence of pain after surgery. Mosbrucker et al. [2] reported that the 3D/HD robotic scope was independently associated with 2.36 times the likelihood of detecting a confirmed lesion, compared to the 2D/HD laparoscope for all types and locations of lesions. Additionally, robotic near-infrared fluorescence with indocyanine green (NIRF-ICG) can help in this detection. Jayakumaran found that robotic NIRF-ICG to 2D detected a statistically significant higher number of lesions when compared to laparoscopic white light (WL) and 3D robotic WL and also resulted in a significant reduction in the postoperative mean pain score [3]. Robotic assistance for DIE seems feasible with good postoperative outcomes in selected patients. Neither conversion to open surgery nor to conventional laparoscopy was necessary. Patients with recto sigmoid involvement can also benefit with robotic assistance [4-6].

Pelvic organ prolapse represents a common female pelvic floor disorder that has a serious impact on the quality of life. Sacrocolpopexy, a surgical procedure that provides adequate support of the vaginal apex is considered the gold standard for repair of level 1 defects of pelvic support, providing excellent long-term results. The advantages of sacrocolpopexy include reduced risk of mesh exposure and denovo dyspareunia, reduced risk of re-operation for symptomatic recurrent prolapse. Moreover, vaginal length is preserved. This procedure decreases the chance of blood transfusion and length of hospital stay. In addition, it has low rate of complication, provides high sexual function and improved urinary, bowel and pelvic symptoms leading to faster recovery and maintaining excellent outcomes.

To Dr. Jennifer Jose, robotic sacrocolpopexy provides the surgeons adequate visualization, dexterity and control; it provides long term symptomatic and anatomic pelvic support to stage III and stage IV prolapse; the wrist of the robotic instruments allows more freedom of motion and improved optics that enables to fully dissect the pubovaginal and rectovaginal spaces through minimally invasive incision. These translate to easier dissection, improved visualization of the promontory, precise suture placement and easier knot-tying with faster learning curve.

Dr. Jose described the key elements of the procedure: the specific length of the mesh is planned the presacral space is exposed and vasculature in the pre-sacral space are identified. The anterior dissection is up to the level of the trigone, the posterior dissection is up to the level of the perineum. Anterior and posterior vaginal mesh placement are placed. Prolene 0 is used about 6 to 10 sutures per vaginal compartment. There are 2 Prolene 0 sutures placed in the sacrum. Robotic sacrocolpopexy gets tricky when the patient had prior abdominoplasty, lung or heart disease, prior abdominal prolapse repair, high body mass index and very small women. Changing the vaginal axis and overcompensating makes a vaginal segment vulnerable. The vaginal axis is important, and lateral enterocoeles are difficult to manage [7,8].

Dr. Joseph Ng delivered a lecture on common complications encountered in robotic gynecologic surgery. His lecture reviewed basic pelvic anatomy and more specifically the relationships of important surgical landmarks to this anatomy, reconstructing how common complications involving the urological, vascular, and colorectal anatomy occur in pelvic surgery. He stressed the importance of recognizing injury as the very first step in the management of these surgical complications. He then went on to demonstrate how gynecological surgeons should manage these complications intraoperatively and in the immediate postoperative period to avoid long term morbidity.

The Role of Robotic Surgery in Gynecologic Malignancy followed the benign gynecology session, chaired by Professor Chi-Heum Cho of Korea, and Dr. Joseph Ng of Singapore.

Since the first approval of robotic surgery in gynecology by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2005, the number of robotic gynecological procedures increased from around 90,000 in 2009 to around 3,2000 in 2019 [9]. Robotic surgery had impacts on both doctors and patients. For doctors, robotic surgery became an integral part of the fellowship training programs. About 40% of the general surgery directors thought that their residents should receive robotic training [10]. Over 60% of gynecologic oncology fellows were allowed to perform robotic procedures in 2015 [11]. On the other hand, a questionnaire study showed that 87% of surgeons experienced physical discomfort during conventional laparoscopic surgery [12]. In the work of Z├Īrate Rodriguez et al. [13], surgeons with different experiences were asked to perform laparoscopic and robotic procedures on surgical models, and robotic procedures were associated with less muscle and mental stress compared with laparoscopic procedures.

For patients, minimally invasive surgery allows same-day discharge [14,15], and the increase in ambulatory surgery was due to the increase of robotic surgery [16]. The advantages of robotic surgery also extended its indications, such as single-port surgery, groin node dissection for vulvar cancer, cytoreduction for ovarian cancer. Finally, Dr. Ka-Yu Tse also highlighted in her talk, the importance of training and guideline development.

Dr. Joseph Noh began his talk by introducing previous studies on learning curve for successful sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping. Studies have shown that it generally requires about 30 cases for a surgeon to reach proficiency level [17-19]. Then he introduced a retrospective review of his institutionŌĆÖs experience in SLN mapping. A total of 119 cases performed since 2017 were reviewed. The success rate for SLN mapping and biopsy was 82.1% and 78.6% for the right and left pelvic lymph nodes, respectively. The most common area of SLN was the obturator area followed by the external iliac area. As he was showing his data, he emphasized the advantages of robotic platform for performing SLN mapping, specifically its high-resolution endoscopic view, and articulation of robotic arms. He also introduced preliminary results of his ongoing cohort studies looking at the incidence of low extremity lymphedema after robotic SLN biopsy. Out of 63 patients whom he followed up until 24 months after surgery, none has shown any evidence of lymphedema occurrence. He and his team are continuing their endeavor with robotic surgery and are now performing robotic vNOTES (vaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery). He closed his talk by stating that further data will be available next year.

Dr. Hung-Cheng Lai delivered a lecture on the evolving role of robotic surgery in endometrial cancer. He highlighted the historical development of robotic surgery and how endometrial cancer represented a unique confluence of patient factors (prevalence of obesity in endometrial cancer patients), surgeon need (the low adoption of straight stick laparoscopy in the majority of operative gynecologic oncology cases), and the incremental improvement in surgical technology (introduction of the technologies like Firefly for ICG identification). He further pointed out how this confluence resulted in a change in practice and how the introduction of robotic surgery resulted in a shift towards minimallyinvasive surgery that did not happen with the introduction of straight-stick laparoscopy.

Dr. Lai also laid out the evolving landscape of clinical practice in endometrial cancer from the change in the role of lymphadenectomy with the ASTEC (A Study in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer) trial [20] to the use of SLN biopsy becoming an established standard of care after the FIRES (Fluorescence Imaging for Robotic Endometrial Sentinel lymph node biopsy) trial [21]. He concluded the lecture by reiterating the importance of finding a coherent pairing of the strengths of robotic surgical technology with the technical requirements and unique demands of a surgical procedure as a pathway to sustainable innovation.

After LACC (Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer) trial, many surgeons believe that MIS may be associated with poorer survival in cervical cancer. An international European observational study, SUCCOR (Surgery in Cervical Cancer Comparing Different Surgical Aproaches in Stage IB1 Cervical Cancer) study, showed that the use of a uterine manipulator in MIS had a 2.76-times higher hazard of relapse [22].

Currently, ongoing randomized controlled trials, RACC (Robot-assisted Approach to Cervical Cancer) and ROCC (Robotic Versus Open Hysterectomy Surgery in Cervix Cancer), study several preventive tumor spillage methods, such as closure of vagina before colpotomy (Fig. 1), and omission of transcervical uterine manipulator during robotic surgery for cervical cancer [23]. Dr. Keun Ho Lee suggests that until conclusive evidence is derived from these trials regarding the safety of robotic surgery for cervical cancer, we have to treat the patients with early cervical cancer carefully.

Finally, ŌĆ£The Future of Robotic SurgeryŌĆØ, chaired by Professor Tae-Joong Kim from Korea, concluded the academic sessions of the meeting.

Since robotic surgery was introduced in Korea, gynecological robotic surgery has grown at a rapid pace. Based on the data so far, robotic surgery is expected to continue to grow in benign disorder and malignancy. Although the use of the robot in cervical cancer has decreased after the LACC trial, it is thought to continue to grow as endometrial cancer increases. Along with the growth of robotic surgery, Dr. Hyewon Chung felt that a large amount of minimally invasive surgeries such as single-site conventional laparoscopy are expected to be replaced by single-port robotic surgery.

Many well-established companies and smaller start-ups have brought to the surface novel systems with unique selling points that aim to displace the market. Approaches and features vary from the introduction of haptic feedback, single port operating, to the implementation of artificial intelligence.

With greater competition in the robotic surgery market, costs of robotic surgical systems and associated instrumentation and maintenance should begin to decline. Nevertheless, a national procurement policy is essential to help drive down costs and ensure equitable access. Furthermore, training schemes and evidence-based strategies must integrate to ensure patient outcomes.

Dr. Joseph Ng delivered a lecture on how to develop sustainable robotic surgery programs and why this is important in contemporary healthcare. He began by outlining a brief history of MIS in gynecology, and explained how robotic surgery filled the gap left by laparoscopy since the introduction of the laparoscopic hysterectomy in the 1980s [24]. Dr. Ng emphasized that how robotic surgery is deployed to serve patients and deliver value is the most important consideration in setting up a robotic surgery program. He used the published experience of the Gynecologic Robot-Assisted Cancer and Endoscopic Surgery (GRACES) program at the National University Hospital [25] as a case study to highlight the key components of a sustainable robotic surgery program which are as follows: 1) identifying a need in the current way that surgical healthcare is delivered and accessed by patients; 2) matching that need to the capability that robotic surgical technology can deliver; and 3) ensuring access to as many patients as possible. This broad access produces two main outcomes: 1) operational efficiency and 2) lower costs.

Surgical simulation is now an essential part of training in any surgical discipline. It allows the development of surgical technique in a safe and supervised environment. Robotic surgical simulation is particularly important because of its differences from conventional laparoscopy and open surgery. Robotic surgical experience is fully immersive, and different surgical techniques required. It is also an important part of standardisation of training for credentialing.

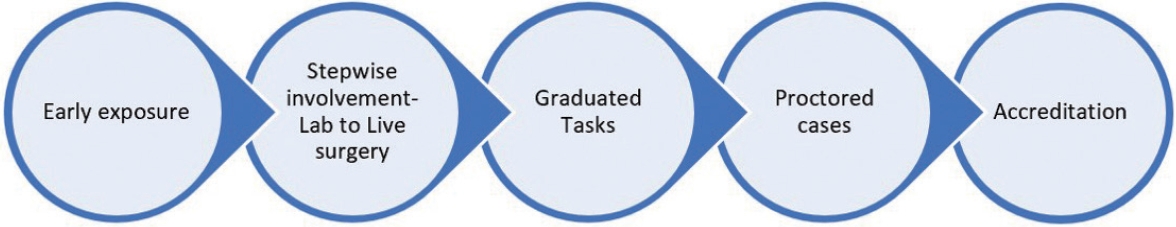

Dr. Jeslyn Wong discussed robotic surgical training programs from other training centres, and also shared the robotic training program in National University Hospital in Singapore. This involved early exposure to the robot, stepwise involvement (from laboratory to live surgery), graduated tasks during live surgery, proctored cases, and accreditation (Fig. 2).

Formal training and assessment are important to ensure safe and sustained growth of a robotics programme. Simulation is a major component of robotic surgical training with face, content, construct and predictive validity. Robotic surgery begins from positioning and docking, dry and wet laboratory simulation and to graduated tasks in live surgery. There must be proper accreditation processes in place to ensure privileges to perform robotic surgery are given to properly-trained and skilled robotic surgeons.

The meeting ended with a round table discussion involving all ASGRS Board Members, outlining the new ASGRS guidelines for Benign Gynecology and Gynecologic Oncology. It was announced that the next ASGRS meeting would be held in Jeju, South Korea, in 2023.

References

1. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Robot-Assisted Surgery for Noncancerous Gynecologic Conditions [Internet]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; c2020 [cited 2022 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/en/clinical/clinicalguidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/09/robot-assistedsurgery-for-noncancerous-gynecologic-conditions.

2. Mosbrucker C, Somani A, Dulemba J. Visualization of endometriosis: comparative study of 3-dimensional robotic and 2-dimensional laparoscopic endoscopes. J Robot Surg 2018;12:59ŌĆō66.

3. Jayakumaran J, Pavlovic Z, Fuhrich D, Wiercinski K, Buffington C, Caceres A. Robotic single-site endometriosis resection using near-infrared fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green: a prospective case series and review of literature. J Robot Surg 2020;14:145ŌĆō54.

4. Lim PC, Kang E, Park DH. Robot-assisted total intracorporeal low anterior resection with primary anastomosis and radical dissection for treatment of stage IV endometriosis with bowel involvement: morbidity and its outcome. J Robot Surg 2011;5:273ŌĆō8.

5. Collinet P, Leguevaque P, Neme RM, Cela V, Barton-Smith P, H├®bert T, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopy for deep infiltrating endometriosis: international multicentric retrospective study. Surg Endosc 2014;28:2474ŌĆō9.

6. Abo C, Roman H, Bridoux V, Huet E, Tuech JJ, Resch B, et al. Management of deep infiltrating endometriosis by laparoscopic route with robotic assistance: 3-year experience. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2017;46:9ŌĆō18.

7. Matthews CA. Correcting pelvic organ prolapse with robotic sacrocolpopexy. OBG Manag 2011;23:31ŌĆō44.

8. Hudson CO, Northington GM, Lyles RH, Karp DR. Outcomes of robotic sacrocolpopexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2014;20:252ŌĆō60.

9. Gitas G, Hanker L, Rody A, Ackermann J, Alkatout I. Robotic surgery in gynecology: is the future already here? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2022;31:815ŌĆō24.

10. Kapadia S, Shellito A, Tom CM, Ozao-Choy J, Simms E, Neville A, et al. Should robotic surgery training be prioritized in general surgery residency? A survey of fellowship program director perspectives. J Surg Educ 2020;77:e245. ŌĆō50.

11. Ring KL, Ramirez PT, Conrad LB, Burke W, Wendel Naumann R, Munsell MF, et al. Make new friends but keep the old: minimally invasive surgery training in gynecologic oncology fellowship programs. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;25:1115ŌĆō20.

12. Park A, Lee G, Seagull FJ, Meenaghan N, Dexter D. Patients benefit while surgeons suffer: an impending epidemic. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:306ŌĆō13.

13. Z├Īrate Rodriguez JG, Zihni AM, Ohu I, Cavallo JA, Ray S, Cho S, et al. Correction to: ergonomic analysis of laparoscopic and robotic surgical task performance at various experience levels. Surg Endosc 2022;36:852.

14. Zhang N, Wilson B, Enty MA, Ketch P, Ulm MA, ElNaggar AC, et al. Same-day discharge after robotic surgery for endometrial cancer. J Robot Surg 2022;16:543ŌĆō8.

15. Sanabria D, Rodriguez J, Pecci P, Ardila E, Pareja R. Same-day discharge in minimally invasive surgery performed by gynecologic oncologists: a review of patient selection. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27:816ŌĆō25.

16. Cappuccio S, Li Y, Song C, Liu E, Glaser G, Casarin J, et al. The shift from inpatient to outpatient hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in the United States: trends, enabling factors, cost, and safety. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:686ŌĆō93.

17. Kim S, Ryu KJ, Min KJ, Lee S, Jung US, Hong JH, et al. Learning curve for sentinel lymph node mapping in gynecologic malignancies. J Surg Oncol 2020;121:599ŌĆō604.

18. Tucker K, Staley SA, Gehrig PA, Soper JT, Boggess JF, Ivanova A, et al. Defining the learning curve for successful staging with sentinel lymph node biopsy for endometrial cancer among surgeons at an academic institution. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020;30:346ŌĆō51.

19. Khoury-Collado F, Glaser GE, Zivanovic O, Sonoda Y, Levine DA, Chi DS, et al. Improving sentinel lymph node detection rates in endometrial cancer: how many cases are needed? Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:453ŌĆō5.

20. ASTEC study group; Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet 2009;373:125ŌĆō36.

21. Rossi EC, Kowalski LD, Scalici J, Cantrell L, Schuler K, Hanna RK, et al. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:384ŌĆō92.

22. Chiva L, Zanagnolo V, Querleu D, Martin-Calvo N, Ar├®valo-Serrano J, C─āp├«lna ME, et al. SUCCOR study: an international European cohort observational study comparing minimally invasive surgery versus open abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with stage IB1 cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020;30:1269ŌĆō77.

23. Falconer H, Palsdottir K, Stalberg K, Dahm-K├żhler P, Ottander U, Lundin ES, et al. Robot-assisted approach to cervical cancer (RACC): an international multi-center, open-label randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019;29:1072ŌĆō6.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 900 View

- 22 Download

- Related articles in Gyne Robot Surg

-

Asian Society for Gynecologic Robotic Surgery: Taking it to the next level2024 March;5(1)

Robotic surgery in gynecology - myomectomy2021 March;2(1)

Trends in robotic surgery in Korean gynecology2020 September;1(2)

Asian Robotic Gynecology Congress 2019, moving closer to the goal2020 September;1(2)